I have this terrible process that I habitually go through with new information: 1) learn it, 2) immediately believe that I've always known it, and 3) wonder what's wrong with everyone else who doesn't seem to know it. This is the process I've gone through with peritoneal dialysis, but I think it's high time that I explain what it is and how it works using the simple layman's terms in which I understand it. If you are a medical professional, please refrain from judging my imperfect education and from harshly correcting any inaccuracies. In fact, maybe you should just stop reading now. For the rest of you, here is what I understand the process to be:

There are essentially two kinds of dialysis: hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis[1] (hereafter referred to as hemo and PD, respectively).

Hemodialysis. Hemo is what most people have heard of/seen, and it's what they think of when they think of dialysis. In hemo, a patient either has a dialysis catheter surgically placed in or near their neck (and running to their aorta, I believe, but don't quote me on that) or they have what is called a fistula developed, which is essentially an engineered building up of large blood vessels in the arm. In either case, a patient typically visits a dialysis clinic three times a week where they connect to a machine that draws out a portion of blood at a time (through the catheter or fistula), cleans it (through a process I know next to nothing about), and then returns it to their body. Over the course of several hours, enough impurities and excess water have been removed from the blood for the patient to be reasonably healthy for the next two or three days.

PD works much differently from hemo in that there is no direct blood interaction at all. This was a relief to me, because when we were first told that Julie would be doing dialysis while she slept, I had a secret, horrifying fear that she could accidentally disconnect a tube by rolling over, and it would shoot blood everywhere, which could possibly be the worst way to wake up. Turns out that this is—fortunately—quite impossible.

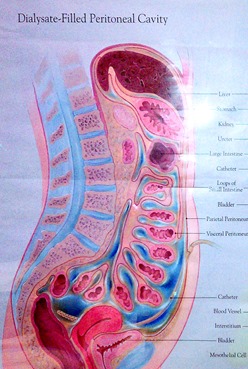

Inside the abdomen is what's called the peritoneum, a cavity bounded by the peritoneal membrane, which is a membrane that lines the outside of most of your internal organs. I'm guessing this membrane is at least a dozen or two square feet, so there is a lot of blood that flows near and through it. This is important, as you'll see in a second.

After the dialysate has had time to "dwell" in the peritoneum for awhile (it

The downside(s). Overall, PD is an easier thing to fit into your life than hemo is since you do it from home on your own schedule. The difficult thing about it

By far, though, the most difficult thing about PD is the risk of developing peritonitis, an infection of the peritoneum. Since the catheter leads directly into the inside of your body, and dialysis is being handled by non-medical professionals (i.e. us), it's somewhat easy to get a small amount of bacteria or dust into the tubing when connecting the dialysate or Julie to the machine. This would almost definitely quickly result in a bad enough infection to warrant hospitalization if not caught within a day or two.

Because of this, whenever we hook everything up, we have to thoroughly wash our hands with antibacterial soap, put on medical masks, close the door, turn off the fan, turn off the a/c or heater, clean connectors with bleach water on gauze, use hand sanitizer, and make the crucial connections as quickly as possible. If any connecting point touches the floor or any non-sanitized thing, we have to throw away everything disposable and start over. It's wasteful but the reasoning is that being wasteful is much cheaper than a hospital stay.

When we first started, it was pretty difficult to get used to. We have more or less gotten used to the idea and the process (albeit grudgingly). But we're still super looking forward to life post-transplant.

And that, ladies and gentleman, is all I know about dialysis. Please direct any questions to a qualified medical professional. Or Wikipedia.

[1] The words peritoneal and peritoneum are pronounced differently from what you may expect. That is to say that it's the second to last syllable that is stressed (i.e. pair-it-oh-NEE-ul, pair-it-oh-NEE-um). This drives me crazy.

No comments:

Post a Comment

You don't need a Google account to comment! Just select "Name/URL" when you click the "Comment as" drop-down menu, and type your name to let us know who you are before you let us know what thought this post inspired in you. No one likes to receive anonymous comments!

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.